Harnessing the Power

Coffee, Java, Jitter Juice, or perhaps you prefer a Mocha? Often styled The Global Addiction, coffee has been integral to modern society for hundreds of years, and rarely do we ever consider the reasons as to why. Originally developed by plants as a means of deterring would be attackers, caffeine as a chemical proved to be an effective insecticide and thus kept the purveyors of this wily drug alive and flourishing when others would die off. Literally. The leaves of plants that contained caffeine would leak the chemical into the soil and cause nearby competitors to wilt early.

The human relationship with this highly effective insecticide is ancient, with legends of the first caffeinated teas being produced in China thousands of years ago. When it comes to coffee, our story can be credibly drawn back to the 15th Century in Yemen, where coffee beans were being imported over from the Ethiopian highlands to be roasted and prepared as a drink; though far more outlandish legends concerning the discovery of this potent stimulant do exist. One has a goat herder noticing that his flock get particularly agitated upon eating the beans raw from the plants, but this story wasn’t written down until 1671 long after the beans had spread their influence. Another story points to a man named Sheikh Omar. While banished from Mocha in Yemen he came upon some caves and tried to sustain himself on some nearby berries. Finding them too bitter he roasted them, but that turned them hard. So then he boiled his roasted beans, which then produced the brown liquid that he then drank and was sustained for days without the need for food. When this miraculous story reached Mocha, he was asked to return and was quickly made a saint.

It is amusing to a modern reader to ponder at the idea that our forebears had to rationalise the effects of caffeine with an act of divinity; but the true scale of the world’s addiction to it is astonishing. Brazil is currently the world’s largest producer of coffee, able to produce up to 35% of the global supply of coffee beans. Coffee has also been an absolute triumph for capitalism; Starbucks is the leader in retail coffee, selling its products through more than 32,000 stores in 83 markets around the world. In 2019, their beverages product category generated 16.5 billion USD, and this is despite the fact that between 65%-80% of all coffee is purchased from a store to be brewed and drunk at home!. Coffee is the most frequently traded agricultural product, and is second only to petroleum in terms of overall commodity trades. We often hear about fluctuations in the price of petroleum globally and how that can have knock-on consequences for just about every aspect of a globalised society, but people rarely consider what would happen if their coffee was suddenly unavailable. We simply need caffeine at this point, and human appetites for coffee are insatiable it seems. But how exactly did these dried beans from Ethiopia become a global addiction? Well, as always, it’s a story about controlling vast amounts of money.

Coffee in the Muslim World

Islam rather famously prohibits the consumption of alcohol (which would itself otherwise be another global addiction were it not for the sheer number of practicing Muslims in the world) for its practitioners, believing intoxicants to be inherently antithetical to their doctrine. Technically, there is some debate on the matter, as scriptures only refer to specific types of alcohol that were made from grapes and palm dates (which would make it mostly about prohibiting wine), but this is considered a minority opinion; the point is clear, that intoxication is to make the body impure and therefore should be avoided. And so it was that when Europe was beginning its transition from the medieval societies of old into the early modern civilisations with a long tradition of imbibing a strong depressant in the form of alcohol, the Muslim world discovered a potent stimulant that didn’t defy the prohibition of alcohol, but it wasn’t without controversy.

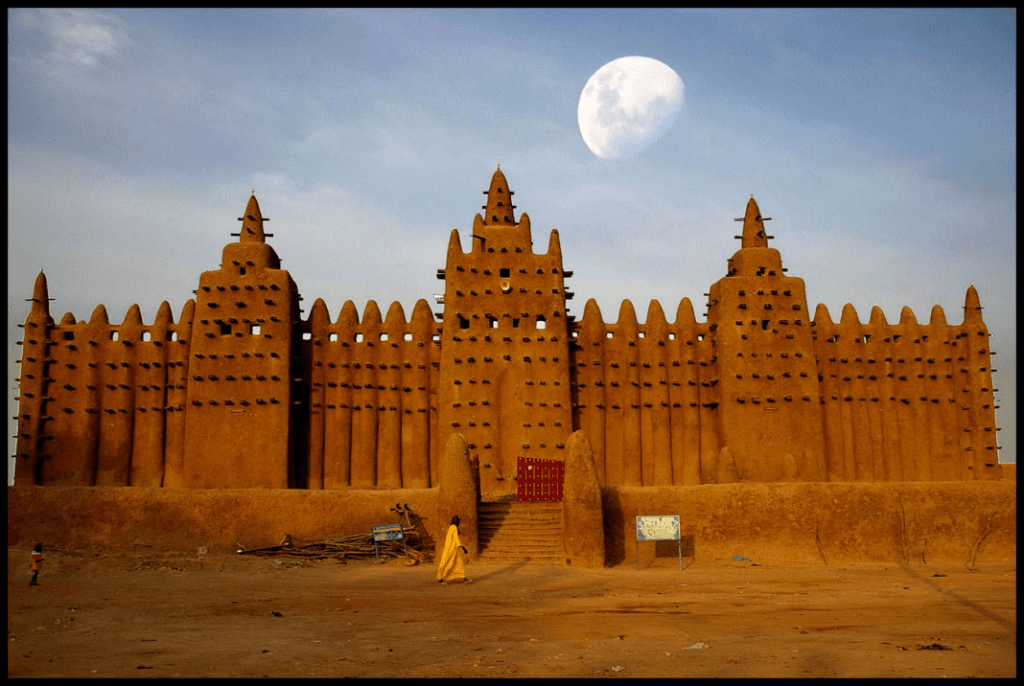

It can’t be denied that caffeine has an obvious effect on the body, it stimulates the mind and if enough is consumed will cause someone to become jittery, and some Islamic leaders in the early 1600s believed this was enough to qualify it for restriction. This was a self defeating problem, however. Once the drink had taken hold in many regions there was simply no rooting it out. Furthermore, while it does have an obvious effect on the body, it is by no means debilitating. Even if one were to hyperfixate on the jitteriness some might experience, what can’t be denied is that it was an extremely important tool. The Islamic world at this time was deeply invested in education and scientific progress. It had long since been a proud tradition of Muslim rulers to invest great amounts of their wealth into universities, mosques, and learning institutions (as exemplified by a previous topic of mine, Mansa Musa the richest man who ever lived). Before coffee, those scholars were limited by what they could achieve before their eyes became too strained from candle light to continue (a problem that was far more significant in an age before lens grinding solved the problem of deteriorating eyesight), but now with this new miracle drug, scholars could work far longer. And, since these scholars were contributing to the legal codes of their regions, coffee did not stay prohibited for very long. Well there was that, and the fact that so many people were already addicted to it. So now the question became, how to make money out of this new miracle drug?

Caffeine in Christendom

Yemen managed to maintain a monopoly on the international coffee trade for a surprisingly long time. This was no mean feat, especially considering the fact that the beans were being imported from Ethiopia at the time. The only way for them to maintain this monopoly was by establishing a strict system by which the beans were sold; all of the beans would have to be boiled BEFORE being sold, which thus made them useless for regrowing once a buyer reached their home destination. Eventually this monopoly was supposedly broken by a Sufi by the name of Baba Budan who smuggled 7 coffee beans out through Mocha and planted them in India. Such was the reverence for this act, that the hill range where he planted the beans was named after him (not just the hill, the entire range of hills around the coffee beans), and, despite only covering this one act of this man’s life, his Wikipedia page has 4 individual references on it.

With the proverbial cat out of the bag, it was time for the Christendom to get their hands on coffee.

The city states of northern Italy historically had firm financial ties with North Africa and the Levant going back to the early crusades, including one infamous incident where the Genoese merchant navy had their ships confiscated so that the crusaders could strip them for materials to build siege weapons in their desperate assault on the city of Jerusalem. To everyone’s surprise, it worked.

Never one to miss an opportunity for fiduciary embiggening, the Venetian merchants were famous for the extent of their maritime commercial empire, and so when the coffee trade started picking up they were quick to start introducing the drink into the rest of Europe. There was initially some backlash among Christian scholars who wanted to ban the “Muslim drink”, but there was a problem: coffee tastes and smells really good, and it’s very addictive. Once coffee was out there, the population that could afford it immediately got hooked, and all protests of the drink were quietly dropped once the detractors actually tried it. The pope even went as far as to declare it a “Christian Drink” in 1600, but Europe wouldn’t see its first dedicated coffeehouse until 1645 when one was set up in the city of Rome. (This is, incidentally, why coffee traditions in Europe tend to stem back to Italian styles rather than the original North African). The British East India Company soon followed suit, and coffee became widely popular in Britain too. Oxford’s Queen’s Lane Coffee House was established in 1654 and is still running today.

And here the story takes a sharp pivot, because all of this discussion of coffee has had a rather light tone to it so far but that no longer really applies to the next stage of the journey that coffee went on. Those who have read up about economics will likely be screaming internally about the key feature of markets; that there is both demand and supply for a commodity. The demand is self-creating, we’ve already discussed how addicted humans are to caffeine, but the supply was severely limited. Whoever could mass produce coffee first would effectively have total control over the market in Europe, and historians among my readers may notice the dates getting closer and closer to some of the darkest periods of European colonialism. And so it was that the Dutch East India Company had an idea that would inspire the suffering of humans on an unimaginable scale as they smuggled a few coffee beans onto their colony on the Indonesian island of Java, and with them thousands of enslaved people to grow them.