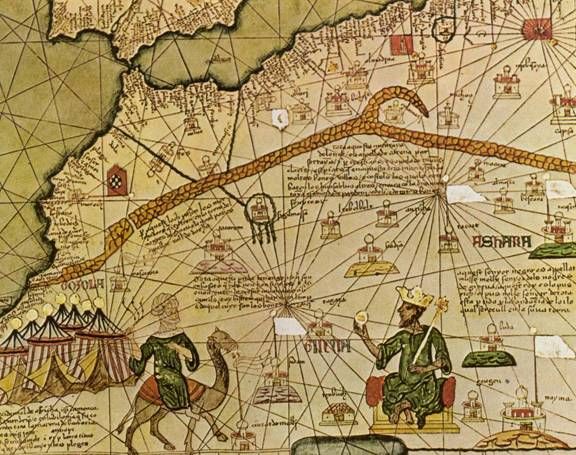

The Mali Empire existed from 1235 to 1670 and became the dominant power in the region of West Africa for most of the middle ages. When it comes to determining the true power of any centralised authority, whether that take the form of a Kingdom, Republic, or City State many look to the so called “hard power” it can exert; the size or aggressiveness of their military, or the gargantuan hoards of gold bullion that can be used to out spend any rival. People think less of the soft power, the unseen institutional changes that can go on to leave the true legacy of any dynasty. Dictators and kings alike come and go, but the laws, the languages, the traditions and the customs linger on for much longer, and so it was that the Mali Empire would go on to set the foundations of West African culture for centuries to come. It’s understandable how such a dynasty is not commonly known among Western Europeans since it all takes place a continent away, but this has many having a historical imagination of West Africa as being nothing but underdeveloped disparate tribes of nomads, when this is far from the truth. Under the Keita dynasty, The Mali Empire flourished and produced unimaginable amounts of gold, which it put to work industriously investing in great building projects like mosques and universities. Far from the underdeveloped backwater nomads of popular imagination, life in West Africa was a highly sophisticated and centralised region, and its legend is best displayed through the infamous pilgrimage of the man who may well have been the richest man who ever lived, Mansa Musa.

When people try to conjure an image of the wealthiest man in the world they tend to think of some titan of capitalism, usually a white westerner, who managed to dominate whatever market they were in. There is clear precedent for this, just look at the Forbes Billionaire list to see how many billionaires fit this description. In recent decades, more and more eastern billionaires have arisen, but rarely do we equate immense wealth with African societies. It surprises many to learn that the man who may well have been the richest person who ever lived was the king of a long since forgotten Empire of Mali in the middle ages, known to us as Mansa Musa, Mansa being the ceremonial title akin to King. The King’s exact wealth is impossible to accurately calculate. The buying power of gold could fluctuate wildly at this time, and there was no hint of any kind of centralised banking or fixed exchange rates, so who can really say what a gold coin was worth in one region to the next, let alone between kingdoms in different continents. The point is that everyone else understood him to be the richest man in the world, and so he was; and this is the story of how the richest man in the world accidentally caused a continent spanning economic recession.

Musa became the ruler of the Mali Empire back in 1312 after his predecessor was supposedly lost at sea. Apparently Muhammad ibn Qu (the previous Mansa) had a fixation with maritime exploration and sponsored two expeditions to sail out into the Atlantic Ocean in attempt to find its edge. People didn’t believe the Earth to be flat at this time, so it has been suggested that this might have been a pre-Columbian era attempt to find land to the West of the Atlantic, another story not commonly known in Europe. Muhammad ibn Qu personally led the second expedition, and nominated Musa to be his deputy until he returned. When he didn’t, Musa became Mansa Musa. This version of events is disputed as the old “whoops, it looks like the previous king is lost forever at sea, I guess that makes me king of all these gold mines” was pretty convenient for Musa (and is even so controversial it has its own wikipedia page), but nevertheless he went on to become one of the most influential figures of the age.

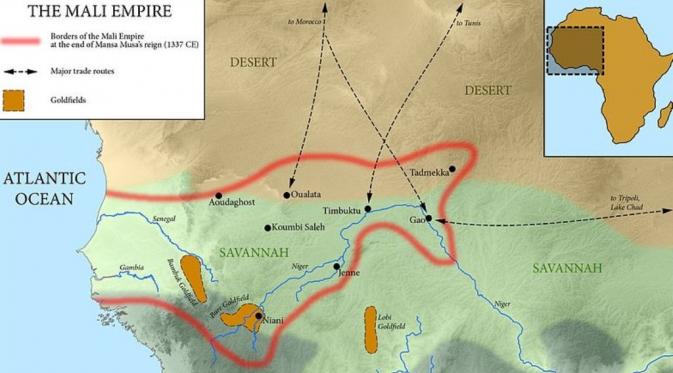

The empire was already fairly prosperous, but under Musa it expanded greatly and encompassed a huge portion of West Africa This land included three huge gold mines, from which Mali is believed to have been the source of half of the gold being traded in what is considered the “old world” (the continents of Africa, Europe and Asia before known contact with the Americas was established). All golden nuggets that were found within the empire were considered the personal property of the Mansa, and were immediately taken to be traded at the imperial court for an equally weighted bag of gold dust. While this was ostensibly done to control the rate of inflation in the empire, in reality it gave the Mansa direct access and control of the most valuable metal in the world and the Mansas of Mali grew to have extraordinary personal wealth.

In addition to the abundance of gold, Mali was able to effectively monopolise trade in Western Africa from Europe to the north and the rest of the African continent to the south. All this was magnified when Mansa Musa brought Timbuktu into the empire, whose financially strategic location by the Niger river gave it unparalleled control of trade for the entire region. Comparatively, Western Europe was struggling financially due to a series of costly civil and dynastic wars that Mali was simply not involved in, and so the wealth of the empire was growing rapidly compared to other contemporaries. There are no modern or historical comparisons that can be accurately made to Mansa Musa’s personal wealth, as one commentator put it: “When no one can even comprehend your wealth, that means you’re pretty darned rich”. Gold was in especially high demand at the time – European Kings were in the practice of debasing their currency in an attempt to pay for their armies, which was causing all kinds of economic bereavements. Meanwhile in Mali, it has been suggested that a year of Malian gold production would produce roughly a ton of gold.

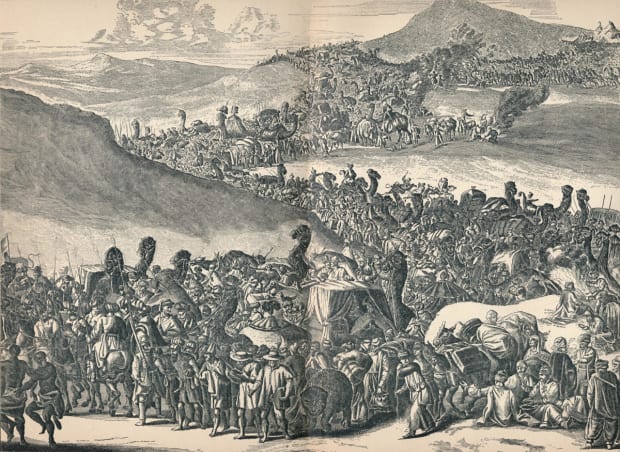

The empire converted to Islam as a result of its interactions with Muslim traders from the east, and would go on to play a huge part in the conversion of much of West Africa. Consequently, in 1324 Musa (and many of the other noble families in the Empire) would take up the Hajj, the practice of undertaking a pilgrimage to Mecca. This wasn’t just a religious expedition for Musa, it had a sharp political angle. Being on the very fringe of the Islamic world at the time Mali was seen as a backwater player with little to offer the central Islamic powers in Arabia. This journey was specifically designed to show off his literally unimaginable wealth and power. Some sources suggested that he had an army of 200,000 men, which would have made it one of the most populated armies in the world at the time and seems unlikely. A more conservative figure for his army was 100,000, which included a corps of elite cavalry units numbering 10,000 horses in all. If either number is true, European Kings wouldn’t be fielding armies of that size for centuries to come.

Whatever the true size of this procession, it would have been unlike anything anyone had seen before. A few accounts have given us precise numbers (the truth of which is still up for debate) and they mention that a train of 100 camels each carried sacks of 135 kilos of gold dust, with another 500 enslaved people each carried a 2.7 kilo golden staff to show off. This was a ludicrous amount of gold, and tales of this pilgrimage would filter out to the rest of Europe as the living King Midas made his way across northern Africa and into Arabia. There was no fixed price of gold in the world at the time, and indeed even within the boundaries of the Mali empire the price could vary between regions, but the sheer quantity of gold on display was enough to get the point across; Mali was not some obscure bit player in Africa, but a serious power in the Arabic world. This procession eventually stopped off in Cairo, where some of his more infamous displays of wealth took place.

When Musa’s party arrived in Cairo, he was summoned to visit the local ruler, al-Malik al-Nasir. Musa was reluctant to take the meeting, initially insisting that he was merely passing through the city but it became clear the main reason he didn’t want to meet al-Nasir was that he would have been forced to pay homage to him, when the whole point of this pilgrimage was to assert his own dominance. To get out of it he gave the Sultan 50,000 golden dinars (this is over 210 kilograms of gold; at the time of writing 1 kilogram of gold is worth around £40,000, making this gift worth £8.4 million in today’s money) as a simple gesture of good faith. Despite this, after much heated debate that nearly spiralled into a full riot in the streets of Cairo, Musa acquiesced and was forced to kiss al-Nasir’s feet anyway.

Musa, in an attempt to show off his wealth, decided to visit the tourist areas and local shops of Cairo. As was the natural inclination of all traders when dealing with ignorant foreigners, the traders were selling their goods at vastly inflated prices. Musa, undeterred, decided to massively over pay for these goods on top of the inflated prices. While well intentioned, he spent so much gold in his time in Cairo that he caused the price of gold to go into freefall and there was a complete crash in the gold market that reverberated across much of the Mediterranean and western Europe. It would be 12 years before the recovery would begin to set in.

The price of gold bullion fell by 20% when compared to silver coins on the market, and a great deal of international trade was disrupted. Cairo was a hub of commerce across the Mediterranean as merchants from all over would stop there and ply their wares. As I mentioned above, the Christian Kingdoms of Europe were already experiencing economic crises as a result of various kings trying to debase their coinage to pay for their ruinously costly wars. One solution to this problem had been Christian merchants importing gold dinars from the Arabic world, and some lords had even gone as far as equipping their mints to make forgeries of these coins (complete with Quranic inscriptions), but now that the price of gold bullion was falling this practice was also coming to an end (that, and the Pope wasn’t too happy about Christians dealing in money that held heretical scriptures on them). Money is often a way to exert soft international power, as it reminded people in Europe of the true wealth of the Arabic world, but now that soft power was failing.

Despite all this, the Mali Empire continued to thrive in the following decades. Mansa Musa took a great deal of inspiration from his tour, and was particularly taken with the idea of Arabic learning institutions. He brought back a great many scholars and invested heavily in the construction of new universities and mosques in his territories. After the pilgrimage, he was able to add many more regions to the empire and spent a great deal of money ensuring that his legacy would be that of a great ruler who changed the world with his vast power for the better of every free person in his empire. Although not well known in Europe today, tales of his vast wealth filtered out to the rest of the old world during his lifetime, and he became an almost mythical figure of the wealth to be found in Africa. Far from the negative stereotypical view that Europeans would take of West Africans in some of the darkest chapters of human history with the trans Atlantic slave trade, Mansa Musa and the Mali Empire stands as empirical evidence of the extent to which a highly sophisticated system of government and culture could thrive in an often overlooked part of the world.