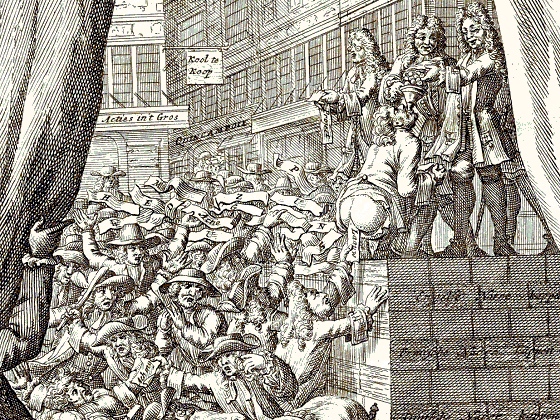

When we left off, tensions were extremely high in England. Some thought was given to hiring foreign soldiers, perhaps from Germany, to try and maintain order as there were some whisperings about the King potentially abdicating in favour of his son, but the British MPs were steadfastly against rash actions with the monarchy. After a half century of extreme political upheaval, no one was keen to revisit the days of the civil war, and so a new way of fighting for political power was devised.

Robert Walpole had managed to stay far enough away from the entire affair so as to not be under any suspicion. He had opposed the speculation on the South Sea Stock (despite then buying a great deal of it, but all that really mattered was public perception at this point) and so was seen as having been above the chicanery of the directors at the South Sea Company. He therefore decided that he would use this opportunity to save the King and his favourites. With key political figures like these in debt to him he would have all of the political capital he would need to realise his own ambitions. Walpole spent 10 days in parliament deflecting calls for punitive action and instead stressed the need for action against the declining credit of the nation, but the House was seeing right through it all. He did succeed in suggesting a proposal to engraft £9,000,000 of south sea stock into the Bank of England just before Christmas and the stock price actually rose from £135 to £210, but after the ministers came back from their break the price had crashed again as the talks fell through.

Parliament responded by setting up a secret committee of 13 members specifically to examine the books of the company directors. Those chosen were known to be staunch anti-company men, including Mr. Archibald Hutchenson, a prominent economist who wrote numerous papers decrying the activities of the Company. Things then escalated to farcical levels when the House of Lords decided that they were going to have their own committee set up, and the directors were forced to scurry between both houses for two separate investigations requiring different evidence at each occasion. The Commons went even further, preventing the directors from leaving the country and each was burdened with a £25,000 bail. The directors didn’t even have legal representation. This was contested, but ultimately overruled on the grounds that their books already showed them to be demonstrably guilty. Nevertheless, parliament entered a state of deadlock. The committees were able to put the screws to the directors, but they stood behind a wall of feigned ignorance that would take considerable work to get through.

All this time, the South Sea Company Chief Cashier, Mr Robert Knight, had done everything he could to change the accounting books. He had torn pages out and rubbed out names, and he even conferred with Blunt daily to try and work out alibis for most of the key players, but Knight was apparently on the verge of a nervous breakdown. If his duplicity was to be discovered, not only would he face trial himself, but anyone he inadvertently took with him when all the evidence he held was made public, he would likely remain at the top of every politician’s kill list for the rest of his very brief life. Knight therefore decided to do the only intelligent thing he could do in this situation: he helped himself to a substantial portion of the company treasury and ran for it. He chartered a yacht to the Low Countries (the modern day area that encompasses Belgium, the Netherlands and other principalities). Rather amusingly he left work on Friday afternoon, and because it was the civil service, no one noticed he was gone until the following Monday morning when a note he had left in his office explaining that he had gone was discovered.

Knight was captured near Brussels (due to his sudden lavish lifestyle on stolen company money), and Emperor Charles VI had been a close ally of the British so it seemed only a matter of time until Knight would be back. And then, nothing happened. As it transpired there was a law in that part of the world that dictated that no one could be extradited from the land in order to face criminal prosecution. This was part of a series of articles of semi-independence seen locally as their own magna cart and dated back to 1354. When British MPs heard this they were furious. For some temporal reference, this is the equivalent of being arrested for celebrating Christmas in 2021 simply because Oliver Cromwell had banned it in 1647 and began enforcing it more strictly in 1655. It was an absurd and massively outdated rule, since Knight had admitted his misdeeds in a note he left behind and there was no question of his guilt, but parliament was powerless.

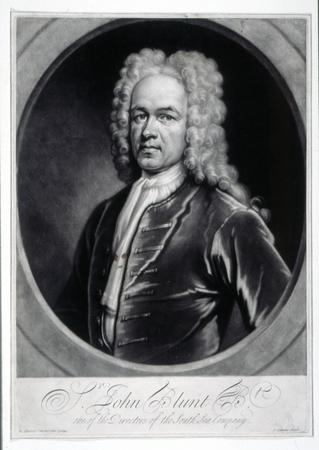

Back in Britain, MPs from both Houses were furious at their inability to get at the one man who could definitively prove exactly where all the corrupt money had been going. Without that Green Book, there was no solid evidence tying the defendants to the scheme, and so the accused simply returned to their best (and so far successful) strategy: stalling. But this was no petty crime, the House of Commons would have its investigation, and so they called on the only remaining man who knew great details of the scheme: Sir John Blunt.

We know precious little about what Blunt was up to in the time between his trip to Tunbridge Wells with his family in August of 1720 and when he was summoned to parliament the following year, but one can imagine him fuming with rage as the scheme finally collapsed and his former allies were turning on him one after another. Perhaps he simply wanted to retire from the infamy of public finances, but when everyone points the finger at you, it’s hard to stay out of the limelight. MPs were keen to get Blunt to spill the beans on the last few key players holding out on their trials, and so he was questioned with the intention of striking a deal to expose the actions of the guilty. He revealed the shocking truth, that Knight had taken the “Green Book” with him; the list of all £1.25million total in bribes and who exactly it was given to.

When it became known that the Green Book could expose all the guilty parties, efforts to retrieve Knight were redoubled, and here we get to some of the wilder speculation of this already farcical tale. Try as they might, no one could get to Knight in the Austrian Netherlands. It seems that someone was pulling the strings from the shadows, even going so far as to move Knight between prisons so that no one could drop in unannounced. When rumours that Knight was missing started to spread, he was suddenly returned to the prison he was allegedly being held in just to be identified, before suddenly disappearing for good. As it happened he wasn’t dead, but he wouldn’t return to England for another six years. Someone had their thumb squarely on the scale, and his name was most likely Robert Walpole.

Walpole knew that if the Green Book made it back to Britain then all the corrupt scoundrels would be prosecuted, and his chief problem was that many of those corrupt scoundrels were needed to keep the government running. What Walpole primarily feared was that if too many Whigs were sent down, the King would be forced to dissolve parliament and call on the Tories to form a new one. He secretly wrote officials in the Austrian Netherlands and stopped just short of flat out offering substantial rewards for them to not release Knight, and under no circumstances allow him to return home. The Green Book was never seen again, and so MPs were unable to follow a proper paper trail when it came to prosecution. Instead they had to resort to cutting a deal with Blunt, and wouldn’t you know it, all of the names Blunt came up with were people Walpole needed to get rid of, and all those omitted were those Walpole needed to keep the government running. We can never know for sure, but this is too much of a coincidence to really be a coincidence.

With no better option, the MPs in the Commons commenced the trials of the accused based on the testimony of Blunt and whatever other evidence that the secret committee was able to find. Some of those who received the bribes were brought before the house, but it was understood that the remaining hundreds of thousands of unaccounted for bribes would require fetching Knight back in order to prove. Incidentally, during this time it came out the the South Sea Company was buying back its own stock to keep the subscriptions selling out, and the directors had sold their own shares at the highest possible price back to the company for personal profit; a practice so obviously immoral and underhanded that retribution from the House was swift and unflinching. A list of names was read out and one after another they were stripped of their financial gains and had their properties confiscated as a way to try and make up the huge deficit caused by the South Sea Company. As the debates rolled on and ministers were each in turn brought before the house, Walpole made his move. Next up on the (currently) proverbial chopping block was the Earl of Sunderland (named Charles Spencer, whose marriage to Anne Churchill created the current Spencer-Churchill line that gave us not only Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the Princess of Wales Diana Spencer Churchill, but also current CEO of Serco Rupert Soames), a man whom Walpole had no love for, but whom he needed to keep the government going.

Walpole stood in his defence, and managed to discredit the two witnesses implicating Sunderland in a matter of £50,000 going to him from the company. He was successful, and Sunderland was acquitted 233 votes to 177. This was an astonishing feat, given just how bloodthirsty the courts had been during this time. Another director, Craggs the Elder and his son (Craggs the Younger) were deeply involved in the scheming, and the Elder had fallen into a deep depression after his son was suddenly killed by smallpox over the winter. Rather than stand before the court and be found guilty as was inevitable, he decided to take his own life the night before he was due to be tried. Absent all sympathy, he was subsequently found guilty anyway.

In the end Blunt was met with the same fate as the other directors. Several MPs spoke up in his defence to allow him to keep a more substantial portion of his fortune on the grounds that he had been promised leniency by the secret committee for his co-operation, but in the end he was only allowed to keep £1,000 from his reported £185,349 accumulated wealth. Later this was appealed and raised to £5,000, which was, rather frustratingly to the observer hoping for justice at the end of this tale, probably a good deal more money than he had started this whole affair with anyway.

At the beginning of all this I promised to tell the story of how Britain got its first prime minister, and it’s finally time for Robert Walpole to step up. The King was in hot water, largely because his mistresses had been so heavily involved with the internal scheming of the company and even had a hand in getting the bill passed through the commons the previous year. He tried to put his support behind the current First Lord of the Treasury, the Earl of Sunderland, but despite being acquitted thanks to Walpole, the Whigs felt that Sunderland was too “unclean” to lead the government at present. Walpole was there to step up, and he simultaneously took over the roles of First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer, the two most senior cabinet positions at parliament. Unfortunately for him at that moment, King George I had a reputation for essentially being a miserable git. His distaste for ruling as King was legendary, and he was immovable in his hatred for the majority of Englishmen. Since Sunderland was the only English man he wanted to deal with, he made Sunderland Groom of the Stole, which, believe it or not, was a cabinet position, and continued to rain favours on him so Sunderland remained the chief minister.

Never one to back away from a challenge, Walpole set to work immediately trying to fix the national crisis. He leaned heavily on the facts that international trade had held steady this entire time, and that there were no wars right now to potentially drain the national coffers (nevermind the fact that all of this debt was to pay for the numerous wars that started all this madness in the first place; all that mattered is that it wasn’t currently getting any worse). His plan was to get what money could still be found and start it moving again, since it was never going to help if it was all locked away. Walpole even managed to find a way out for those in debt; they could pay 10% of their capital owed and forfeit their remaining holdings, allowing many to escape the dark cloud of suicides sweeping the nation. Against all odds, and with careful strategy, the coggs of the British economy kept turning, and at an excruciating pace people began to recover.

This is in stark contrast to what was going on in France. John Law decided this was the perfect time to return to Britain (again, he had killed a man in a duel but when you’re that influential trifling matters such as a man’s death are no more than obstacles to be overcome) and seek out a royal pardon. I suppose he was finding it difficult to live in France with the angry mobs looking for his blood. In the wake of the disaster that he had caused on the French financial system, the french government had taken a completely different course of action to the British. The Nobles there were furious at the idea that some people had made money speculating on the stock market. People were forced to reveal exactly how much they had gained from speculation, and those who had previously been poor (the lords were all exempt from both taxation and this now speculation bill) were heavily fined up to 90% of their possessions. This was blatant authoritarianism. The speculators had not committed a crime and had been very much encouraged to speculate, yet now they were being severely punished for it. The English political elite chose instead to persecute the directors of the company, going some way to explain why France would soon have the extremely bloody revolution and the relatively libertarian England would not.

So after all this madness and chaos, where did we end up? A few of the extremely and obviously guilty parties were put on trial and had some money taken away, but those with the political capital to spend were able to simply walk away. No real change swept the nation, and very little accountability was assigned for the ruination of a generation of people in Britain nor the suicides of so many. Sunderland passed away in 1722, and in 1723 Walpole became Britain’s de-facto prime minister, setting the record for the longest term in office (which at 20 uninterrupted years has yet to be beaten) and the trend of the majority party having a Prime Minister that lives on to this day. Blunt died in relative wealth thanks to a pension from his son in bath 1733. This pension had largely been funded by the wealth he had gained speculating on South Sea Stock, so it wasn’t much of a punishment. The generation that would follow this would be defined by their apathy for authority. Those in power had swindled the entire nation, and the young had no interest in seeing that happen again. Occasionally angry mobs would storm into the lobbies of the House of Commons demanding reparations, but these were all quickly dispersed under threat of violent reaction from the authorities.

“First you pick our pockets, then you send us to gaol for complaining!”

An anonymous protestor whose words were recorded in the Commons lobby

I’m surprised this story isn’t better known, as it follows Britain into the financial situation that would ultimately lead to immense pressure on international commerce and the eventual colonisation for which it would become so infamous globally. Perhaps it’s because it makes British political figures look bad, or perhaps it’s because frankly teenagers don’t want to read about stock market trades in a classroom, but I hope with these articles I can impress upon you just how much the story of money has shaped our modern world.