When the bill to hand over the lion’s share of the national debt to the South Sea Trading Company had passed through parliament a year prior, there was intense emotion across the political landscape of England. Those close to the venture, but more so those who stood as direct beneficiaries of its success, cheered the dawning of a new age of national finance and exploring the outer limits of the art of the possible. There were, of course, detractors. Although the bill had passed the House of Commons it came under fire in the House of Lords (among them Robert Walpole, who nevertheless went on to buy up plenty of shares for himself early on), for being a pursuit of enriching the few while leaving the many impoverished. How this particular irony was lost on them is quite unclear. Nevertheless, the bill passed, and for the summer of 1720 John Blunt and his fellow schemers had free reign to do with the market as they pleased as just about everyone believed they were all benefitting from the stock market, holding dear to the oldest of beliefs that a rising tide raises all ships. To put it bluntly, no one was prepared for the devastating blow the company’s crash would have to the entire country.

Blunt did not take long to begin his blatant breaking of the agreements with parliament over the issuing of company shares. The South Sea Company had a deal with the government to issue one share for every £100 of government debt that it was issued, but the first announcement of a subscription of shares being sold came in April 1720, before the official stock swaps were due to take place. Shares were already trading at above £100 so right from the beginning Blunt was openly flaunting the agreement in search of profit. Here’s how it worked: at the time of these transactions, the shares were actually trading for £300, not £100, which means that for every £600 of government debt the company only had to sell 2 shares instead of 6, with the remaining 4 now being sold off for profit. This was so successful and the stock price continued to rise so much that he decided to try again, issuing another 10,000 shares on April 30th at £400 a share. Calculating inflation rates for this period is difficult as the British currency was still tied to the gold standard, this meant that as the price of gold fluctuated so too did the value of the currency. To give you a rough idea of the amounts of money we are talking about with these transactions, £100 in 1720 is very roughly the equivalent of about £10,000 today.

By the standards of the day this was unethical because he was announcing these surplus sales too early, banking on the inflated stock price at the time to maximise his profits. And yet, Blunt faced no repercussions. In fact, as we explored last time, Blunt had many of the most influential political figures not only on his payroll, but had also tied their financial fortunes to that of the company. It was because of these agreements behind closed doors that the average people of Britain were speculating on what they were convinced was a legitimate trading company that could one day rival that of the titan of colonialism that was the East India Trading Company (even the name was evocative). Today, one might expect industry insiders, journalists, and whistleblowers to raise the alarm at what an obviously untenable financial position the company was in. It barely managed to maintain any position at all in the transatlantic slave trade and was sending a single ship a year, subject to heavy duties at Spanish ports, to South America. There was simply no way for the company to make any profit, let alone enough profit to actually pay dividends to the shareholders. Journalism was still a relatively new concept, and what little reporting there was on these obvious issues was extremely limited. Even when it came to the collapse of the Mississippi Company and rioting in France newspapers in Britain barely give it a mention, or if they did they reported very limited information with next to no investigative work done on Law himself. The appetite to see this company fall simply wasn’t there, and when King George I himself had been made chairman, it was given official royal prestige and it almost became one’s patriotic duty to speculate on the market. The beauty of the whole scheme was that no one could be forced to swap their debt for shares, and so there was no need to spend any money enforcing this. People simply wanted to buy in and be part of the great national craze.

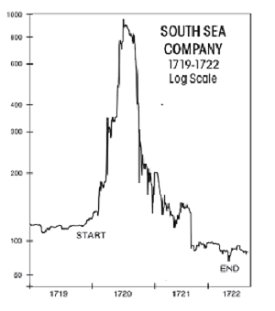

Blunt became obsessed with raising the stock price, seemingly believing that he could inflate it infinitely and with it bring Britain’s entire finances back on track. He seemed to have been taken in by his own hysteria just as much as anyone else. Over thirty seven thousand shares had been sold off for a total of £12,750,000, but most of the sales were just down payments, which (when deducting the bribes) only left him with £1.5million, but Blunt was only just getting started. He insisted that instead of setting aside the money to meet the £7.5million they promised the government they should instead be used to loan money to people to buy South Sea Company Stock. People could borrow £250 per £100 of stock held, with a maximum of £3,000 per person. In this way, over £1million was raised and the stock price rose to £400 at first, but from May 19th to June 2nd the price rose even higher to £800 per share. Shortly after this the price began to waver. investors had already made a considerable profit, including King George, who sold off a lot of his shares before heading off back to Hanover to spend the summer there. He had bought £20,000 worth of shares and sold them off for £106,500 a few months later, the perfect example of the fortunes to be made through speculation, but while the King had plenty of income to gamble on the stock market, by offering credit, Blunt was enticing the more vulnerable of society to risk their life’s savings on his scheming. This was, quite frankly, bordering on madness. Blunt was about as close to paying people to buy shares in the South Sea Trading Company as he could get without being exposed as the emperor sans his clothing. From this point onwards, no longer would it only be the established wealthy members of society buying these shares, but now people without the means to financially recover from potential losses were wracking up significant debt to buy into a company with no reasonable hope of ever being successful enough to see a return on their investment. By this time the credit available to the company was £5million, but no provision had yet been made to actually generate the £7.5million needed to pay the government for the privilege of setting up the scheme in the first place. To deal with this, Blunt pulled off his most outrageous plan yet.

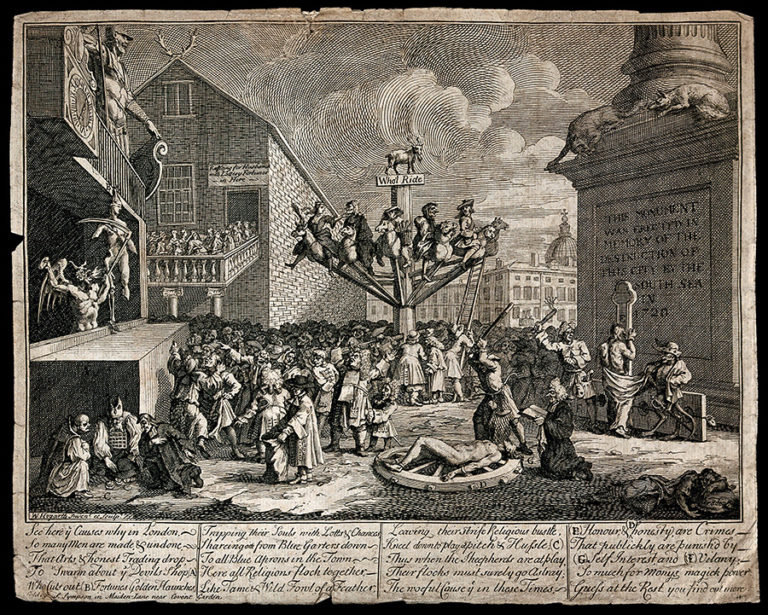

A third subscription was set up, this time with the outrageous price of £1,000 per share (25% higher than the price the shares were trading for at the time). He brought out his usual theatre and made this offering the most attractive yet; only 10% deposit was required, with the rest being paid off in 10% installments every 6 months. The entire lot sold out and the company made £5million from that subscription alone. Over and over they kept doubling down, believing the price could rise forever, and more money was still being loaned out to people in much the same way as had happened in France with the Mississippi Company. The Board of Directors had changed the upper loaning limit to £5,000 per person, but Blunt was ignoring this and had allowed many of the senior lords at court to borrow well in excess of the limit and up to £100,000 in the case of John Gumley.Even their one time arch rivals the Bank of England was getting in on the scheme of lending people money to buy their shares, raising their own price from £200 to £265 from May until October that year. Change Alley became a regular circus of activity as people from all walks of life queued up to secure credit and join in the frenzy. The bubble was expanding rapidly, and no one seemed in any mood to ask what would happen when it stretched too far.

The good times would not last, however. The problem the company faced was that it had taken in £8.5 million, but had loaned almost all of it out. It was due £60,0000,000 in installments, but it was extremely doubtful that this much money could be found in the entirety of the country by this point. This is what caused Blunt to become so nervous about the supply of money that he forced his hand into the market and requested that Lord Townsend issued writs against rival financial institutions to ensure that people could only buy stock in his company. His plan backfired enormously, and the entire market entered freefall. Blunt was trying everything possible (and indeed impossible) to keep the price high. On August 30th the Board of Directors announced an absurd 30% dividend by Christmas, and annual dividends of 50% every year afterwards. This was obviously impossible, and was yet another shock to investors. Even back of the napkin maths led people to realise that the company would need to be making profits in excess of the entire market value of all other joint-stock companies each year and the company was yet to make any profit at all. The price was high for a few days as this was being worked out, but by early September the stress on the demand for money was too great and the price began tumbling. On September 1st, the stock traded for £770, on the 9th it was £575, and then by the 19th it was just £380. The Board even had to resort to begging the Bank of England to help, with Robert Walpole helping to mediate a contract between the two companies. By 24th of September the demand for money was so bad that the Hollow Sword Blade company had to close shop forever, forcing the share price even further down. Needless to say, the deal with the bank was off.

People were ruined. Anyone who had borrowed money (which was almost everyone) was utterly unable to pay or sell off their shares, and so huge swathes of society were utterly collapsing. Several lords were left penniless, and had to beg the king for new employment. The Duke of Portland was so impoverished he had to leave the country and applied to be a colonial governor. He was given Jamaica, but died not long afterwards. The Gentry was hit far worse owing to the amount of credit they had to take on to buy these shares. Most lost their properties, gentlemen had to seek work and their daughters were now seeking employment as governesses, but of course no one had any money to pay them. A wave of suicides struck the nation. It had become commonplace for newspapers to be filled with notices of gentlemen who had killed themselves due to being completely unable to get out of the ruinous financial position they were in. It seemed that all along people had been aware of the scheming going on behind the scenes, but now the price was falling, and suddenly these practices were being heavily scrutinised. People wanted blood, rumours and speculation of the directors’ greed ran like wildfire through the press. Things got so bad that when the king returned to reopen parliament in November, he found a country heavily charged against him and the company, and he was accused of conniving with the directors. The share price also fell from £210 to £135 on the very day he arrived back in England. The South Sea Bubble had finally burst, and in its wake an entire generation had been ruined.